Dividend Paying Stocks Have Appeal But Don’t View Them As Bonds

Conservative investors have historically invested in dividend-paying stocks to generate income and increase stability in their portfolios. The ability of these companies to pay a dividend is viewed as a sign of current financial strength and a forward-looking sign of positive expectations for growth and earnings, a perfectly reasonable assumption.

However, many investors make the incorrect assumption that a dividend means a guaranteed return for an individual stock investment and view these income streams similarly to bonds. As long as they see the quarterly dividend payment into their accounts, investors are content. Unfortunately, these investors forget that income is just one component of return, with the other being price return. They often ignore the price movement because they feel they are getting paid to wait through a higher dividend yield if the price drops.

This gets taken to the extreme in the case of investments like MLPs or REITs that offer a yield upwards of 10%, an eye-popping number in this environment where the 10-year treasury yields about 3.2%. It’s as if the holy grail of investing has been achieved: equity like returns with bond like volatility. However, as with many things in the investment world, there is no free lunch.

General Electric is a recent example of this misconception costing investors. GE has always taken pride in their stable dividend and countless investors have relied on this consistent payout for years. Recently, GE has undergone significant business changes including the divestiture of multiple business lines and now a third CEO since 2017 after operating for years with a toxic balance sheet. While the company’s stock has been hit hard the last two years, the latest blow came on October 30, when GE announced earnings and slashed their dividend to $0.01 per share. That’s right 1 penny per share. Just a year ago, GE paid a $0.24 per share dividend in the fourth quarter.

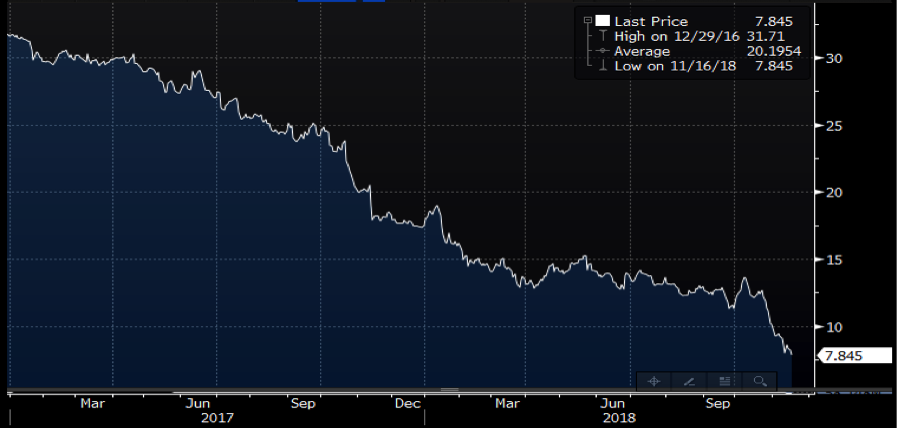

GE’s recent share price declines are captured in the chart below:

Since GE made the dividend-cut announcement, the stock is down roughly 30% in just over two weeks. Moreover, GE has dropped a whopping 70% in price since the beginning of 2017.

GE stock averaged a yield of 4.21% on a quarter-over-quarter basis during that same timeframe, after starting 2017 at 3%. The increase in dividend yield during this time can be attributed largely to the significant drop in share price, further deceiving investors with this dividend-only mindset. All told, the dividend return is dwarfed by the plunge in the price of GE’s stock from over 30 to below 8 today.

For comparison, on January 1, 2017 the 2-year treasury yielded 1.21%. Therefore, an investor looking at these two investments at that time may have been swayed by the 3-4% dividend yield of GE and just simply assumed they could clip that income and earn 3-4%. However, GE investors learned the hard way that this was not the case.

While the slower horse from a yield perspective, the bond investor is going to come out ahead at the end of this scenario. Of course, it’s not always going to happen like this and this is a very specific, extreme example of a dividend paying stock suffering a significant price decline. But this plummet came after GE experienced years of financial stability and growth, showing that it can happen to any company at any time.

All told, we believe there are a couple important lessons to take away from this story:

- Dividend Payouts Don’t Mean Guaranteed Return

Owning dividend paying stocks for income is a common objective for many investors. But it’s extremely important to remember that when a stock pays a dividend, the stock price adjusts by the corresponding level of the dividend. For example, if a $10-dollar stock pays a $1 dividend, the stock is now priced at $9. This occurs in order to preserve the investment value of the stock. Instead of owning 1 share at $10, investors now own $1 in cash and 1 share of a stock valued at $9.

As previously mentioned, when companies pay a consistent dividend, it’s viewed as a sign of confidence and trust as the company has enough in excess earnings to return capital to shareholders. However, as seen with GE, even while they continued to pay out dividends, their shareholders were losing money. Even worse, the moment the dividend was reduced, that trust in the company was quickly lost as evidenced by the accelerated decline in share price.

- Dividends Don’t Last Forever

Dividends can be raised or lowered at any time at the discretion of a public company’s board of directors. Higher dividends entice investors and are interpreted as a positive sign as mentioned before. However, the dividends can be slashed at the first inclination of trouble and companies can get by defending it as a business decision.

A bond investment must be looked at completely differently. First, most bonds are issued with a fixed coupon (payment) that does not change, regardless of the price. Secondly, bond issuers are legally obligated to repay their debt holders. In the event they don’t pay, the consequence is often default or downgrade, significantly handicapping the corporation or municipality from borrowing in the future. Thus, a stream of income from a bond is considerably more durable.

For conservative investors, we believe return of capital is more important than return on capital. High dividend yields on individual stocks may look inviting, but often include company specific risk, market risk and a host of other perils.

Individual bonds, on the other hand, have a set maturity or call date in the future where investors receive their principal investment back. We believe the term “clip the income” is more applicable to these investments, as the income is received without dinging the price and principal is safely returned. Dividend paying stocks don’t offer such a guarantee.

Investors looking to balance their portfolio and achieve an income target should favor investment grade bonds over dividend paying stocks. Peace of mind cannot be underrated, especially in the wake of market volatility. You don’t want a 3-4% yield to end up with a 60% loss. While a rare case, it’s substantially more likely to happen in an individual stock than a bond.